Friday, August 16, 2013

Monday, August 5, 2013

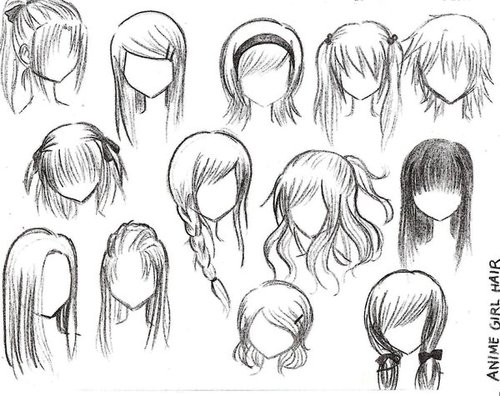

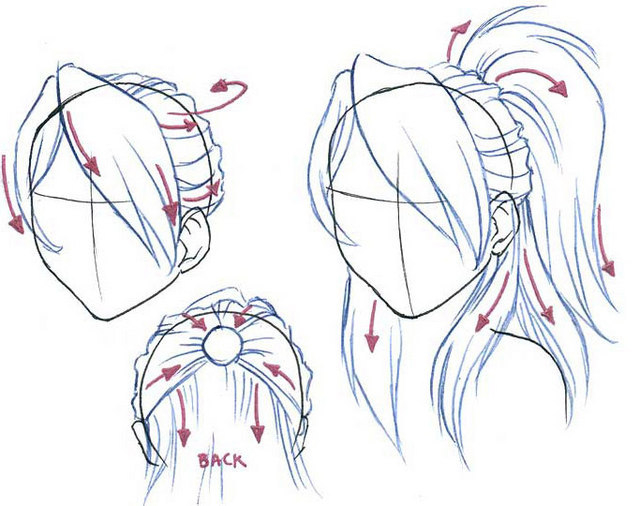

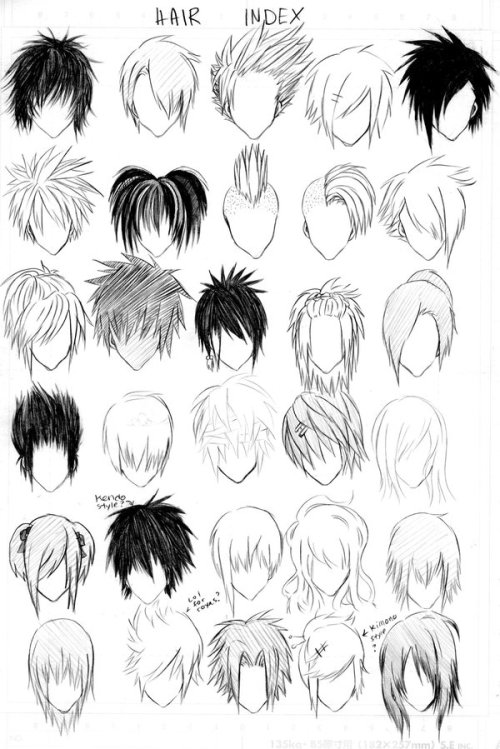

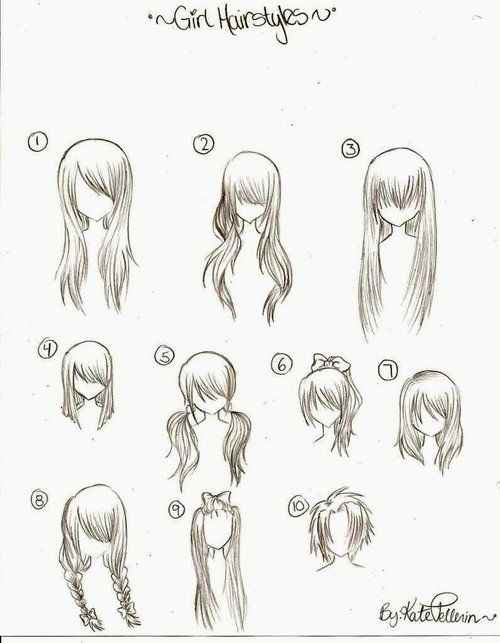

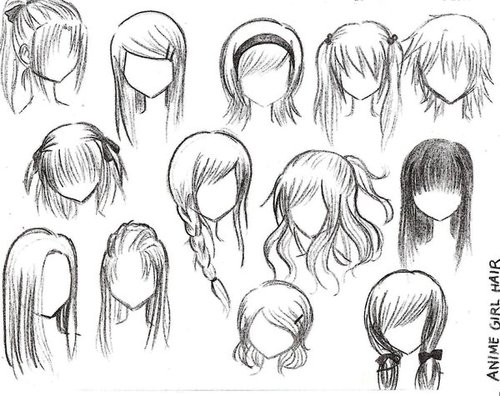

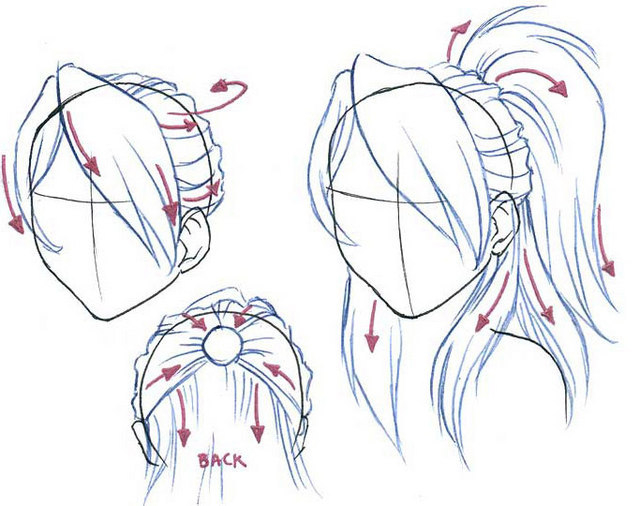

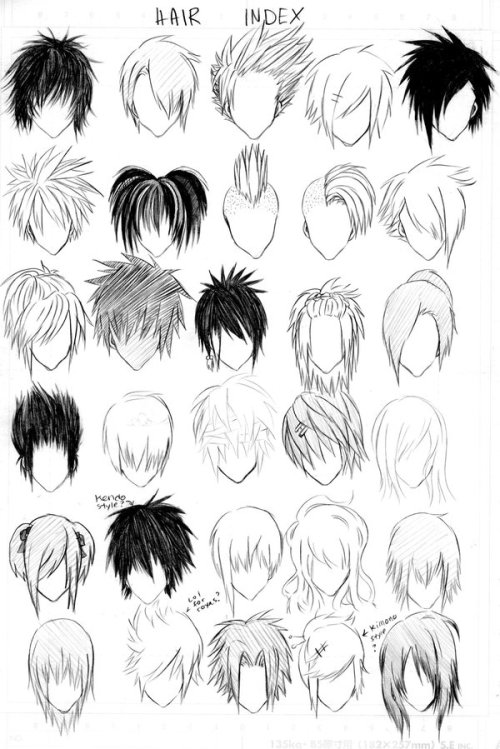

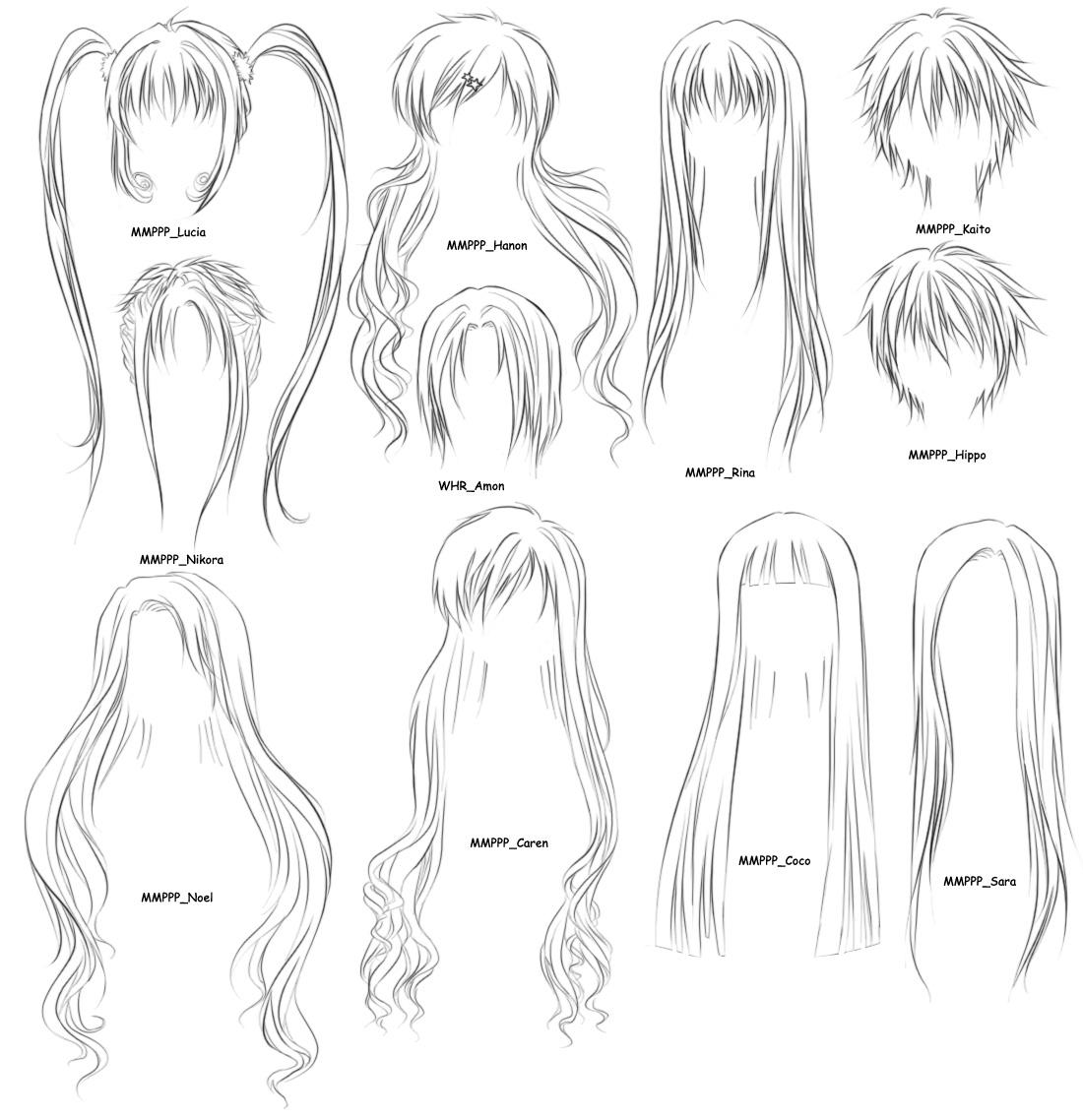

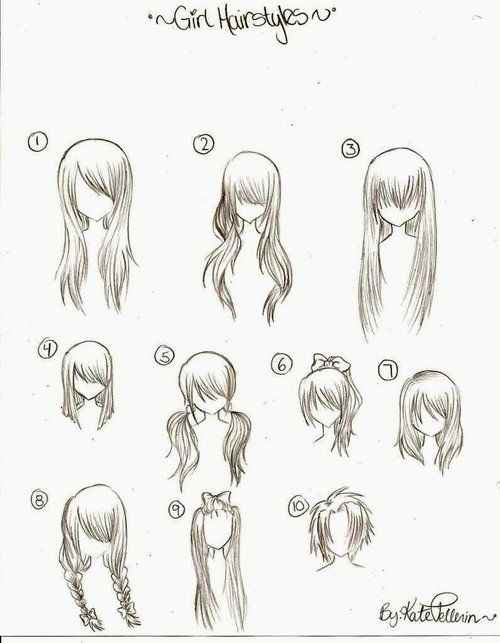

How to create anime hair..

Konichiwa, I'll going to 'teach' yawl how to draw an anime hair..

Atcually, not teaching.. Showing a pic of anime hair..

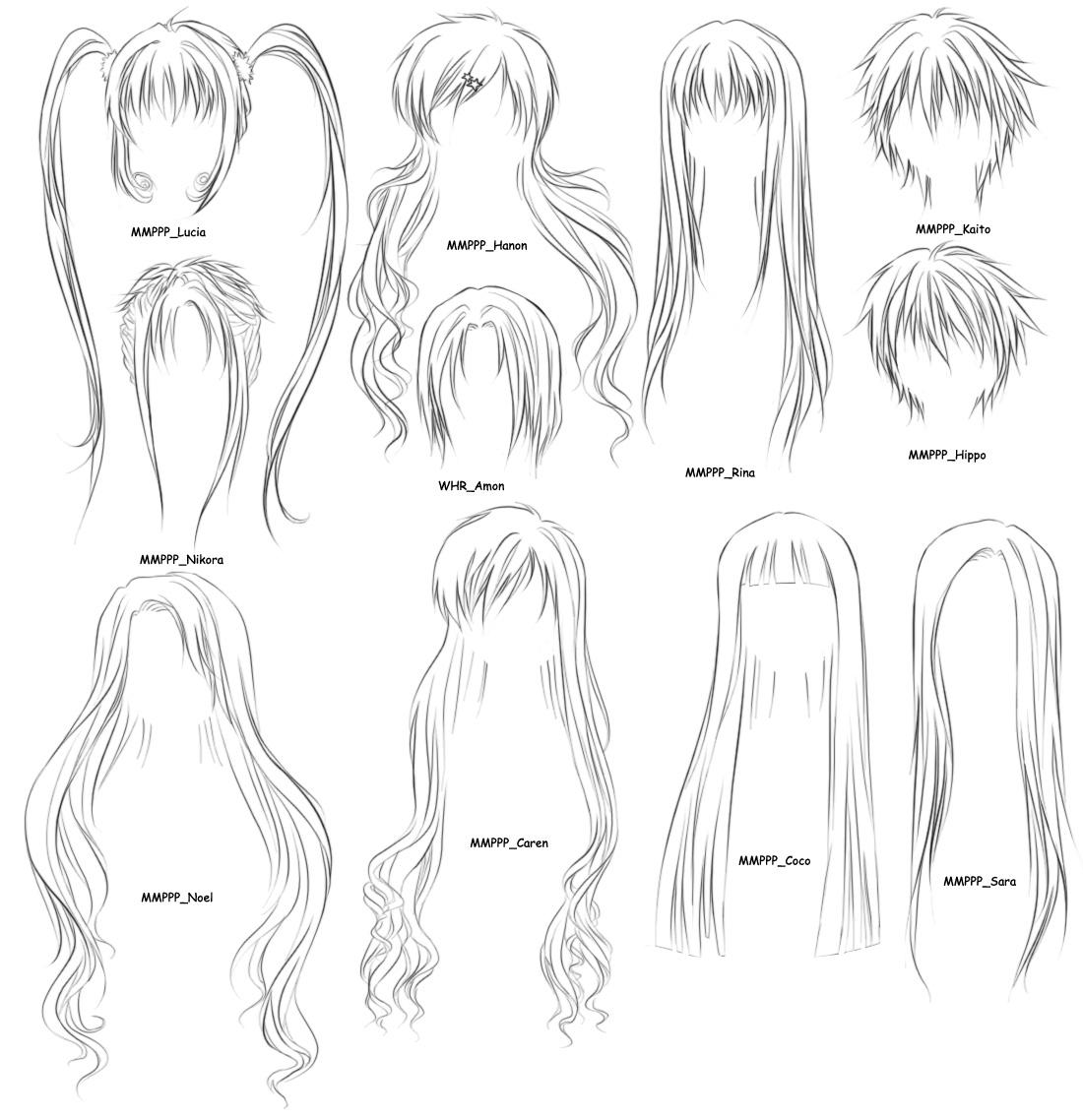

Hair of anime: Mermaid Melody..

That's all for today..

Sayonara.!!

Atcually, not teaching.. Showing a pic of anime hair..

Hair of anime: Mermaid Melody..

That's all for today..

Sayonara.!!

Anime music video..

An Animation music video (AMV) is a music video

consisting of clips from one or more animations set to an audio track

(often songs or movie/show trailer audio); the term usually refers to fan-made unofficial videos. An AMV can also be a set of video game

footage put together with music which is known as a GMV. A newer format

of AMVs including or comprising only non-anime or gaming footage called

animashing has also started to gain popularity.[citation needed]

AMVs are not official music videos released by the musicians, but are rather amateur fan compositions which synchronize edited video clips with an audio track. AMVs are most commonly posted and distributed informally over the Internet. Anime conventions frequently run AMV contests or AMV exhibitions. While AMVs traditionally use footage taken from anime, video game cut-scene footage is also a popular option.[1] Music used in AMVs is extremely diverse, using such genres as J-Pop, rock, hip hop, pop, R&B, country, and many others.

AMVs should not be confused with music videos that employ original, professionally made animation (such numerous music videos for songs by Iron Maiden), or with such short music video films (such as Japanese duo Chage and Aska's song "On Your Mark" that was produced by the film company Studio Ghibli). AMVs should also not be confused with fan-made "general animation" videos using non-Japanese animated video sources like western cartoons, or with the practice of vidding in Western media fandom, which evolved convergently and has a distinct history and fan culture. "Anime music videos" are a sub-genre of the more general "animated music videos". Parallels can be drawn between AMVs and songvids, non-animated fan-made videos using footage from movies, television series, or other sources.

The first anime music video was created in 1982 by 21-year-old Jim Kaposztas.[2] Kaposztas hooked up two VCRs to each other and edited the most violent scenes from Star Blazers to “All You Need Is Love” by The Beatles to produce a humorous effect.

One of the first anime music videos that achieved popularity came from the 1996 song "Daytona 500", from rapper Ghostface Killah, using clips from the 1960s anime Speed Racer, which was first shown on English television back in 1968.[citation needed]

While an ordinary AMV is just one movie used along with a song, animashes are a type of AMV where multiple films are used, often mixed together using maskings and chroma-keying tools. Thanks to these tools, some animashers create crossover AMVs/animashes. Most Western fans that make AMVs use Disney movies, or other movies of that nature (for example, Universal or DreamWorks movies). Some of the most popular Disney films used in AMVs are the Lion King, Lady and the Tramp, Bambi, Brother Bear, Fox and the Hound, etc. CGI movies, such as Legend of the Guardians, Happy Feet, Rio, and How to Train your Dragon have also recently become popular movies used in AMVs. AMVs and animashes have become a very popular group of people on YouTube, and many animashers have become very well known for their creative style. Some animashers work together on an AMV/animash, which is called a collab. Other times, one animasher hosts something called a "Multi Editor Project" or M.E.P. for short, in which many different animashers each take a part of a song and put their parts together to create a diverse AMV/animash.

The question has been raised of how such works can continue to exist, or such organizations to flourish, when they do so with questionable legality. The answer is that many of the Japanese authors encourage it—several of these authors began their careers with the same kinds of projects they witness anime fans working on today (ex. Clamp).

It seems that American anime distributors hold a similar sort of view in regards to AMVs. In an interview with site AnimeNewsNetwork, FUNimation Entertainment copyright specialist Evan Flournay said they generally see AMVs as a sort of free advertising. "The basic thinking going into fan videos is thus: if it whets the audience's appetite, we'll leave it alone. But if it sates the audience's appetite, it needs to come down. Does that make sense?" he says.[7][8]

In recent years there has been an increased demand, primarily on the part of the record industry, for the removal of AMVs from sites like YouTube, Google Video, or the AnimeMusicVideos.org aggregation site, with particular regard to YouTube due to its relative popularity compared to other AMV sources, as well as its for-profit status. Musical performers and their representative record labels have been requesting the removal of some music videos from websites where they are made available for download, though it is primarily the latter who take such action. Public discussions and perspectives give varying accounts of exactly how widespread these actions have become. In November 2005, the administrator of AnimeMusicVideos.org was contacted by Wind-up Records, requesting the removal of content featuring the work of the bands Creed, Evanescence, and Seether.[9] Songs on AMVs uploaded on YouTube are sometimes removed due to copyright infringement of either TV Tokyo or the Warner Music Group.

While music labels and corporations generally see AMVs in negative light, often the actual musical artists in question do not hold the same views. A number of AMV editors report to having had positive contact with various artists, including Trey Gunn and Mae.[10] Japanese electronic duo Boom Boom Satellites even teamed with site AMVJ Remix Sessions to sanction an AMV competition to help promote one of their singles, going so far as to provide the source material for editors to use. The winner's video would be featured during one of the pair's tours. The first of this competition took place in January 2008 using the song "Easy Action" and the anime movie Vexille.[11] A second competition took place later that year in November using the song "Shut Up And Explode" and the anime Xam'd: Lost Memories.[12]

In his book Code: Version 2.0 and a subsequent talk in Google's AtGoogleTalks Author's Series,[13] Creative Commons founder Lawrence Lessig specifically mentions AMVs as an example when dealing with the legality and creative nature of digital remix culture.

AMVs are not official music videos released by the musicians, but are rather amateur fan compositions which synchronize edited video clips with an audio track. AMVs are most commonly posted and distributed informally over the Internet. Anime conventions frequently run AMV contests or AMV exhibitions. While AMVs traditionally use footage taken from anime, video game cut-scene footage is also a popular option.[1] Music used in AMVs is extremely diverse, using such genres as J-Pop, rock, hip hop, pop, R&B, country, and many others.

AMVs should not be confused with music videos that employ original, professionally made animation (such numerous music videos for songs by Iron Maiden), or with such short music video films (such as Japanese duo Chage and Aska's song "On Your Mark" that was produced by the film company Studio Ghibli). AMVs should also not be confused with fan-made "general animation" videos using non-Japanese animated video sources like western cartoons, or with the practice of vidding in Western media fandom, which evolved convergently and has a distinct history and fan culture. "Anime music videos" are a sub-genre of the more general "animated music videos". Parallels can be drawn between AMVs and songvids, non-animated fan-made videos using footage from movies, television series, or other sources.

The first anime music video was created in 1982 by 21-year-old Jim Kaposztas.[2] Kaposztas hooked up two VCRs to each other and edited the most violent scenes from Star Blazers to “All You Need Is Love” by The Beatles to produce a humorous effect.

One of the first anime music videos that achieved popularity came from the 1996 song "Daytona 500", from rapper Ghostface Killah, using clips from the 1960s anime Speed Racer, which was first shown on English television back in 1968.[citation needed]

Contents

AMV creation

The creation of an AMV centers on using various video editing techniques to create a feeling of synchronization and unity. Several techniques are available to achieve this:- Editing: Using different clips from the video source and changing between them at specific times is the most important tool the AMV creator has. Often both the events in the video and the transitions between the clips are synchronized with events in the music. This synchronization is divided into two general types: internal and external. Internal synch involves synching the audio with actual events taking place in the scene, such as gunshots and slamming doors. External synch is instances of edited in cuts made in time with the audio.

- Digital effects: Using video editing software (commonly a non-linear editing system) the video source can be modified in various ways. Some effects are designed to be imperceptible (such as modifying a scene to stop a character's mouth from moving) whereas others are intended to increase synchronism with the audio, or possibly create a unique visual style for the video.

- Lip-sync: the synchronization of the lip movements of a character in the original video source to the lyrics of the audio, to make it appear as if the character were singing the song, often the purpose is comedic. Lip-syncing is also commonly used in parody AMVs. These songs usually come from musicals, or to the latest on the pop charts.

- Some editors use original and manipulated animation, both two-dimensional and three-dimensional, in AMV works. Such additions are often used for visual effect or to convey a story that is otherwise incommunicable using only the original video source.

- Rubber-bands, keyframe manipulation or dissolves: These are techniques in which the editor makes points in a video source on the timeline of the non-linear editing program that they can drag to different positions which makes the video either fade in or fade out. This can be to another video clip, or to a different color, most commonly solid black or solid white.

Popularity

John Oppliger of AnimeNation stated that fan-produced AMVs are largely popular with Western fans however not with Japanese fans. One reason he cited was that Western fans experience a "more purely" visual experience as most Western fans cannot understand the Japanese language, the original language of most anime, and as a result "the visuals make a greater impact" on the senses.[3] The second reason he cited was that because Westerners are "encouraged by social pressure to grow out of cartoons and comics during the onset of adolescence" whereas Japanese natives grow up with animation "as a constant companion", English-speaking fans tend to utilize and reconstruct existing anime to create AMVs whereas Japanese fans "are more intuitively inclined" to create or expand on existing manga and anime.[4]While an ordinary AMV is just one movie used along with a song, animashes are a type of AMV where multiple films are used, often mixed together using maskings and chroma-keying tools. Thanks to these tools, some animashers create crossover AMVs/animashes. Most Western fans that make AMVs use Disney movies, or other movies of that nature (for example, Universal or DreamWorks movies). Some of the most popular Disney films used in AMVs are the Lion King, Lady and the Tramp, Bambi, Brother Bear, Fox and the Hound, etc. CGI movies, such as Legend of the Guardians, Happy Feet, Rio, and How to Train your Dragon have also recently become popular movies used in AMVs. AMVs and animashes have become a very popular group of people on YouTube, and many animashers have become very well known for their creative style. Some animashers work together on an AMV/animash, which is called a collab. Other times, one animasher hosts something called a "Multi Editor Project" or M.E.P. for short, in which many different animashers each take a part of a song and put their parts together to create a diverse AMV/animash.

AMV competitions, evaluations, and rankings

- Iron Editor: Two or more editors compete directly with one another, editing videos on the fly in a real-time contest in the style of Iron Chef. Most commonly these bouts go for the length of one or two hours and they are held either in person, at an anime convention, or over the Internet. In both cases there are designated judges who compare the videos, either by the theme, the timing or overall production quality of the videos made during the competition. Judges will declare a winner and most commonly this winner goes on to compete against other editors who have won previous parts of the competition. The other alternative is an individual Iron Editor competitions, in which there is only one part to the competition and most commonly only two editors, only one of whom wins.

- AMV Viewer Choice: The editors submit videos to competitions that are held either at anime conventions or on Internet websites. In both cases the winners are decided by the viewers and sometimes the editors themselves are allowed to vote. In conventions AMVs are usually judged by the category they are competing in, for example an action video would compete with other action videos. Viewers watch the videos and they submit votes at the end of the viewing portion of the competition. The other way that this competition is held, is through an Internet website. Some websites have a similar way of judging the AMVs, by the category they are in. While on other websites the videos compete against other videos of the same or different categories and are judged on which is a better AMV overall, not solely on the theme of the video. The site AnimeMusicVideos.org has the largest known annual AMV contest, the AnimeMusicVideos.org Viewers Choice Awards.

- In March 2008, Tokyopop hosted the I-Manga Music Video Mash Up Contest. The contest called for fans to create a music video, using Tokyopop manga and music. As opposed to most anime music videos, I-Manga Music Video Mash Up Contest required participants to animate and manipulate still images with the use of motion graphics. The contest featured art from Bizenghast and Riding Shotgun with music ("Feel the Disease" by Kissing Violet, "Break Ya Self" by Far East Movement). The winner of the contest was awarded an iPod Video, loaded with Tokyopop music and Tokyopop I-Manga webisodes. As well as featured placement on Tokyopop's YouTube channel.[5]

- There are several public rankings of AMVs available: A-M-V.org StarScale (only for registered users), A-M-V.org Opinions Top10% (only for registered users), AKROSS Rating, AMVNews Overall Ratings

AMV and copyright infringement

The Japanese culture is generally permissive with regard to the appropriation of ideas. Works such as dōjinshi, unauthorized comics continuing the story of an official comic series, are actually encouraged by many anime makers.[6] These dōjinshi take an original copyrighted work and expand upon the story, allowing the characters to continue on after, before, or during the original story. Most anime makers encourage this practice, as it expands their series. Some see it as a tribute while others see it from a business viewpoint that it draws in more support for the anime than it would have had otherwise. Some manga artists create their own dōjinshi, such as Maki Murakami's "circle" Crocodile Ave (Gravitation).The question has been raised of how such works can continue to exist, or such organizations to flourish, when they do so with questionable legality. The answer is that many of the Japanese authors encourage it—several of these authors began their careers with the same kinds of projects they witness anime fans working on today (ex. Clamp).

It seems that American anime distributors hold a similar sort of view in regards to AMVs. In an interview with site AnimeNewsNetwork, FUNimation Entertainment copyright specialist Evan Flournay said they generally see AMVs as a sort of free advertising. "The basic thinking going into fan videos is thus: if it whets the audience's appetite, we'll leave it alone. But if it sates the audience's appetite, it needs to come down. Does that make sense?" he says.[7][8]

In recent years there has been an increased demand, primarily on the part of the record industry, for the removal of AMVs from sites like YouTube, Google Video, or the AnimeMusicVideos.org aggregation site, with particular regard to YouTube due to its relative popularity compared to other AMV sources, as well as its for-profit status. Musical performers and their representative record labels have been requesting the removal of some music videos from websites where they are made available for download, though it is primarily the latter who take such action. Public discussions and perspectives give varying accounts of exactly how widespread these actions have become. In November 2005, the administrator of AnimeMusicVideos.org was contacted by Wind-up Records, requesting the removal of content featuring the work of the bands Creed, Evanescence, and Seether.[9] Songs on AMVs uploaded on YouTube are sometimes removed due to copyright infringement of either TV Tokyo or the Warner Music Group.

While music labels and corporations generally see AMVs in negative light, often the actual musical artists in question do not hold the same views. A number of AMV editors report to having had positive contact with various artists, including Trey Gunn and Mae.[10] Japanese electronic duo Boom Boom Satellites even teamed with site AMVJ Remix Sessions to sanction an AMV competition to help promote one of their singles, going so far as to provide the source material for editors to use. The winner's video would be featured during one of the pair's tours. The first of this competition took place in January 2008 using the song "Easy Action" and the anime movie Vexille.[11] A second competition took place later that year in November using the song "Shut Up And Explode" and the anime Xam'd: Lost Memories.[12]

In his book Code: Version 2.0 and a subsequent talk in Google's AtGoogleTalks Author's Series,[13] Creative Commons founder Lawrence Lessig specifically mentions AMVs as an example when dealing with the legality and creative nature of digital remix culture.

Im An Otaku!!!

Konichiwa, Hi everybody!! Im crazy today cauze the post of today is.. 'Im An Otaku!!!'

Yes, thats me. Im an otaku..

What is otaku?

Short:

A fan of anime and manga..

Long:

Otaku is derived from a Japanese term for another person's house or family (お宅, otaku). This word is often used metaphorically, as an honorific second-person pronoun. In this usage, its literal translation is "you". For example, in the anime Macross, first aired in 1982, Lynn Minmay uses the term this way.[1][2] The modern slang form, which is distinguished from the older usage by being written only in hiragana (おたく) or katakana (オタク or, less frequently, ヲタク), or rarely in rōmaji, appeared in public discourse in the 1980s, through the work of humorist and essayist Akio Nakamori. His 1983 series An Investigation of "Otaku" (『おたく』の研究 "Otaku" no Kenkyū?), printed in the lolicon magazine Manga Burikko, applied the term to unpleasant fans in caricature. Animators like Haruhiko Mikimoto and Shōji Kawamori had used the term among themselves as an honorific second-person pronoun since the late 1970s.[2] Supposedly, a set of fans kept using it past the point in their relationships where others would have moved on to a less formal style of address. Because this misuse of the word otaku indicated social awkwardness, Nakamori chose the word itself to label the fans.

Another source for the term comes from the works of science fiction author Motoko Arai. In his book Wrong about Japan, Peter Carey interviews the novelist, artist and Gundam chronicler Yuka Minakawa. She reveals that Arai used the word in her novels as a second-person pronoun, and the readers adopted the term for themselves.[citation needed]

In 1989, Tomohiro Machiyama wrote a book called Otaku no Hon (おたくの本 lit. The Book of Otaku?), which delved into the subculture of otaku and has been claimed by scholar Rudyard Pesimo to have popularized the term. Machiyama himself has said that the book's popularity was due to its publishing coincidentally the same year as the arrest of Tsutomu Miyazaki, "The Otaku Murderer."[3]...

Despite the negativity, in Japan the moe-related content was worth ¥88.8 billion ($807 million) in 2003, while some estimated the market could be as much as ¥2 trillion ($18 billion). In 2004 the Nomura Research Institute put the number of otaku in Japan at 2.85 million people.[8] Japan based Tokyo Otaku Mode a place for news relating to Otaku has been liked on Facebook almost 10 million times.[9]

The former Prime Minister of Japan Taro Aso also claimed himself to be an otaku, using this subculture to promote Japan in foreign affairs.[10] In recent years some "idol otaku" have been naming themselves simply as Wota (ヲタ?) as a way to differentiate from traditional otaku. The word was derived by dropping the last mora, leaving ota (オタ?) and then replacing o (オ?) with the identically sounding character wo (ヲ?), leaving the pronunciation unchanged.[11]

The district of Akihabara in Tokyo has been a notable attraction center for otaku where maid cafes have been set up where waitresses dress up and act like maids or anime characters. Akihabara also has dozens of stores specializing in anime, manga, retro video games, figurines, card games and other collectibles.[12] In Nagoya, students from Nagoya City University started a project on ways to help promote hidden tourist attractions such as the otaku culture to attract more otaku abroad to the city.[13]

Okay, that's all that I now..

Yes, thats me. Im an otaku..

What is otaku?

Short:

A fan of anime and manga..

Long:

Otaku is derived from a Japanese term for another person's house or family (お宅, otaku). This word is often used metaphorically, as an honorific second-person pronoun. In this usage, its literal translation is "you". For example, in the anime Macross, first aired in 1982, Lynn Minmay uses the term this way.[1][2] The modern slang form, which is distinguished from the older usage by being written only in hiragana (おたく) or katakana (オタク or, less frequently, ヲタク), or rarely in rōmaji, appeared in public discourse in the 1980s, through the work of humorist and essayist Akio Nakamori. His 1983 series An Investigation of "Otaku" (『おたく』の研究 "Otaku" no Kenkyū?), printed in the lolicon magazine Manga Burikko, applied the term to unpleasant fans in caricature. Animators like Haruhiko Mikimoto and Shōji Kawamori had used the term among themselves as an honorific second-person pronoun since the late 1970s.[2] Supposedly, a set of fans kept using it past the point in their relationships where others would have moved on to a less formal style of address. Because this misuse of the word otaku indicated social awkwardness, Nakamori chose the word itself to label the fans.

Another source for the term comes from the works of science fiction author Motoko Arai. In his book Wrong about Japan, Peter Carey interviews the novelist, artist and Gundam chronicler Yuka Minakawa. She reveals that Arai used the word in her novels as a second-person pronoun, and the readers adopted the term for themselves.[citation needed]

In 1989, Tomohiro Machiyama wrote a book called Otaku no Hon (おたくの本 lit. The Book of Otaku?), which delved into the subculture of otaku and has been claimed by scholar Rudyard Pesimo to have popularized the term. Machiyama himself has said that the book's popularity was due to its publishing coincidentally the same year as the arrest of Tsutomu Miyazaki, "The Otaku Murderer."[3]...

In Japan

In modern Japanese slang, the term otaku is most often equivalent to "geek".[4] However, it can relate to a fan of any particular theme, topic, hobby or any form of entertainment.[5] The term otaku can be applied to both males and females. For example, Reki-jo are female otaku interested in Japanese history. While the word is used abroad to mean a fan of anime and manga who enjoys the anime culture, in Japan, the word can be looked down upon as a term for a person with any obsessive interest (not confined to anime and manga) in particular some cases reaching extreme levels such as men falling in love with Dakimakura (Body Pillows). "When these people are referred to as otaku, they are judged for their behaviors - and people suddenly see an “otaku” as a person unable to relate to reality".[6][7]Despite the negativity, in Japan the moe-related content was worth ¥88.8 billion ($807 million) in 2003, while some estimated the market could be as much as ¥2 trillion ($18 billion). In 2004 the Nomura Research Institute put the number of otaku in Japan at 2.85 million people.[8] Japan based Tokyo Otaku Mode a place for news relating to Otaku has been liked on Facebook almost 10 million times.[9]

The former Prime Minister of Japan Taro Aso also claimed himself to be an otaku, using this subculture to promote Japan in foreign affairs.[10] In recent years some "idol otaku" have been naming themselves simply as Wota (ヲタ?) as a way to differentiate from traditional otaku. The word was derived by dropping the last mora, leaving ota (オタ?) and then replacing o (オ?) with the identically sounding character wo (ヲ?), leaving the pronunciation unchanged.[11]

The district of Akihabara in Tokyo has been a notable attraction center for otaku where maid cafes have been set up where waitresses dress up and act like maids or anime characters. Akihabara also has dozens of stores specializing in anime, manga, retro video games, figurines, card games and other collectibles.[12] In Nagoya, students from Nagoya City University started a project on ways to help promote hidden tourist attractions such as the otaku culture to attract more otaku abroad to the city.[13]

Okay, that's all that I now..

So, Sayonara!!!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)